Lauded composer Philip Krumm has been at the center of multiple significant art movements.

In addition to performing with 20th-century masters and having his own music catalogued in multiple releases, he's been a decades-long creative catalyst for San Antonio — a metro not always on the cutting edge. Krumm organized the city's first concerts showcasing "new music" composers such as John Cage, helped drag it kicking and screaming into the psychedelic '60s and eventually provided a stage for some of its greatest literary minds.

It's a role the 82-year-old has embraced with a wink and a smile.

"Phil is a genius, a real genius," says Louis Cabaza, keyboardist for The Children — a band that emerged as San Antonio's chief psychedelic '60s export — and later for Grammy-winning singer-songwriter Natalie Cole. "You could almost hear him thinking. I always thought if there were people from outer space — travelers — it'd be him."

In the late 1950s, while still a teen, Krumm and a fellow San Antonio musician hosted a series of DIY concerts at the fledgling McNay Art Institute, premiering works by John Cage, Richard Maxfield and others now revered as some of the last century's most significant composers.

Eventually, Krumm went on to work with Cage and other icons — Yoko Ono and Karlheinz Stockhausen among them — and contributed to two of the most significant 1960s art movements, the ONCE Group and Fluxus.

Later, Krumm helped usher in the Alamo City's 1960s counterculture. He programmed the innovative Youth Pavilion at Hemisfair '68, founded the city's first psychedelic light-show company, managed rock bands and hosted parties at his apartment that were attended by Beat writers Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs.

"The '60s were amazing," Krumm says. "It was like Paris in the '20s. Boundaries breaking down, creativity exploding. Not sure you'll see anything like it again."

After the seismic '60s, Krumm's life slowed down a bit. But even then, he remained a creative force, running San Antonio bookstores including Clipper Ship Book Store and King William Books. He also helmed the award-winning Musica Nova radio program at long-running classical music station KPAC-FM.

Still witty and sharp in his eighth decade, Krumm is one of San Antonio's living links to the giants of the 20th-century avant garde. But for all his brilliance, and all the effort he's made to move the city ahead, he hasn't reaped much financial reward.

Krumm is surviving on a modest social security check and living in a portion of the house he inherited from his family. Until recently, was losing his vision. After a year of battling the health system, he's regained his sight thanks to cataract surgery.

His road hasn't been an easy one, but this is often the case for those in the vanguard.

The recent inclusion of Krumm's work in "Jerry Hunt: Transmissions From the Pleroma," an exhibit of composer-performer Hunt's sculptures and video at New York's prestigious Blank Forms Editions, could bring a renewed — and long overdue — focus back to this overlooked icon.

Portrait of the artist

Krumm was born in Baltimore in 1941, the son of a union organizer father and mother who funneled her talents as an aspiring writer into penning ad copy. H.L. Mencken, one of the 20th century's most famous literary critics, was a family friend. However, due to young Philip's health problems, the Krumm clan relocated to San Antonio's more favorable climate.

After a childhood immersed in music — he was a Stravinsky fan by age 5 — the teenaged Krumm became assistant to the librarian for the San Antonio Symphony and overheard rehearsals of innumerable classical works. He also worked for the San Antonio opera and met some of the era's stars.

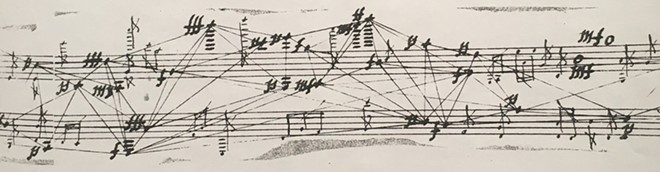

Eventually, Krumm's insatiable musical appetite led him to "new music," a movement that employed dissonance, chance and electronics to expand classical music's boundaries. It was often performed in a playful, deliberately confrontational manner.

"Part of the fun of new music was seeing who you could get rid of first," Krumm said in 2015 to the blog Astronauta Pinguim. "Who would be the biggest chicken? Who would be the first one out? I know I took pride in running people out of the auditorium when I got the chance."

Partners in crime

Krumm's early partner in stretching San Antonio's musical sensibilities was Robert Sheff, later known as "Blue" Gene Tyranny. The late piano prodigy went on to become a respected composer in his own right and toured supporting artists including Iggy Pop.

"He was so brilliant," Krumm says of Sheff. "Just an astonishing piano player. Could sight read anything — I mean anything — at age 16, and just got better."

Krumm and Sheff organized a series of new music concerts at the fledgling McNay Art Institute, Texas' first modern art museum. Eager to jumpstart the series, a fearless Krumm reached out to his hero John Cage directly.

"I got interested in Cage's stuff and wrote a letter to his Stony Point address. Which, at that time, was just 'John Cage, Stony Point, New York.' There were no ZIP codes," Krumm says. "His publisher sent me a wad of scores."

Through the McNay concerts, Krumm and Sheff connected with the greatest avant-garde musicians of the era — Terry Riley, Richard Maxfield, La Monte Young and Tom Constanten, the latter of whom later found fame as a member of the Grateful Dead.

"I met the other guys from the Grateful Dead, but I can't remember their names anymore," Krumm says with a sly grin.

Those McNay concerts remain unprecedented in Texas music history, according to observers.

San Antonio native and music critic Andy Beta, who has written for Pitchfork and the New York Times, says he was stunned to learn about Krumm's concert series when he was commissioned to write the liner notes for the composer's 2003 album Formations.

"Growing up in San Antonio, the McNay was this stuffy institution," Beta says. "To think that the work of distant luminaries had world premieres down in Texas — staged by two teenagers nonetheless — still feels inspiring. That these two teens took it upon themselves to disrupt the status quo, to startle, to try and shock life into the populace is important ... . And I hope it inspires another Texas teenager to take it upon herself to envision and enact a different present and future."

Harsh critics

The first guy through the wall always gets bloody, or so it's said. Given his eagerness to overturn the status quo, Krumm was no exception.

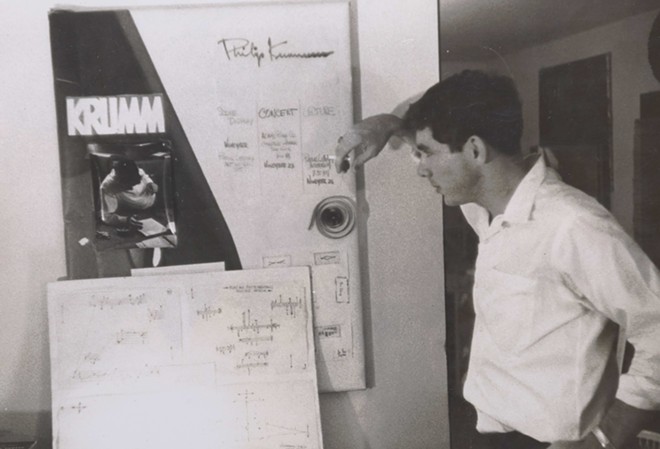

As Krumm began showcasing some of his own works, which relied on dissonance and unconventional scoring techniques, the now-defunct San Antonio Light ran a full-page attack on his work. In the article "Krummy? It's Simply 'New Music'," critic Glenn Tucker excoriated the young creator, even fabricating absurd titles to mock his compositions.

"When young San Antonio composer Philip Krumm sits down to play, some people laugh," Tucker wrote. "Children usually weep."

From the perspective of our jaded, seen-it-all 2022, it's difficult to imagine a fledgling composer generating such vitriol, much less any kind of attention in the mainstream press.

Asked about the piece now, Krumm shakes his head.

"What an asshole. Capital 'A,' capital 'H,'" he says of Tucker. "But you have to put up with that kind of stuff if you're doing really radical art." Gerald Ashford, a critic at the Express-News, also weighed in with the absurdly titled but more sympathetic article "Young S.A. Pioneers: Pair Deny Efforts to Abolish Music."

"These young men talk a bewildering amount of good sense," Ashford wrote about Krumm and Sheff. "[They] are not trying to destroy music but only try to extend its scope ... [to] expand the limits of what is to be considered music. And perhaps that is not such a bad idea, if you stop and think about it."

Already composing challenging new works, Krumm graduated from Jefferson High School in 1960 and entered the St. Mary's University music program on a full scholarship.

However, more resistance awaited.

"It was a very conservative time," Krumm says. "There were well-meaning people, but St. Mary's wasn't that great in 1960. It's much better now."

During one performance on campus, heckling gave way to physical violence.

"I was doing a La Monte Young piano piece and I was under the piano — had to knock on the bottom of it — and some joker shoved a chair into my kneecap pretty hard. Can you imagine somebody caring that much about ... that? That's just being an asshole. But that's a lot of what I put up with back then, because it was all brand new!"

Despite the adversities, some understood what Krumm was doing.

His innovative score for a community theater production of The Taming of the Shrew drew admiration. At the urging of theater proprietor Bill Larsen, Krumm sent the score to Ross Lee Finney, then head of the music department at the University of Michigan.

Finney loved it.

Though Finney couldn't guarantee Krumm a spot in Michigan's graduate school program, he encouraged the young composer to make the journey. So, with only $39 to his name and a train ticket bought with borrowed money, Krumm arrived in Ann Arbor in late 1961. He was accepted into grad school and awarded a President's Award grant. His leap into the unknown paid off.

"It was hard to make anything move much down here. But it was good people," Krumm says. "Going from St. Mary's to Ann Arbor was like being on a spaceship."

'Music for Clocks'

In Michigan, Krumm finally found a welcome environment for his radical musical approach.

"It was transcendental," Krumm recalls. "I was in the right place at the right time, and that was the best thing that ever happened to me — being in Ann Arbor."

Krumm immediately became involved with the ONCE Festival of New Music, a gathering of composers who performed their own works in defiance of unsupportive local institutions — an approach strikingly similar to his own McNay concerts.

ONCE allowed Krumm to work alongside John Cage, who directed a performance of Toshi Ichiyanagi's "Sapporo." Cage had Krumm "play" a bicycle, the Japanese avant-garde composer's favorite means of transportation. Krumm used a bow to draw sounds from the spokes and the wheels.

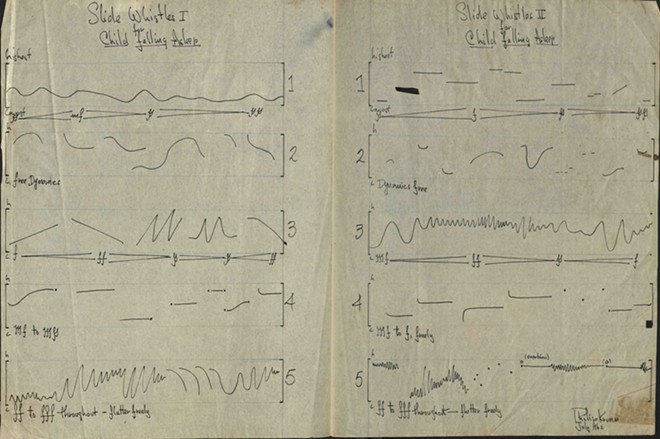

Krumm premiered several of his own compositions at ONCE, including the well-received "Music for Clocks," a proto-minimalist composition with a Dada spirit. The stage was filled with clocks, which were the music's intended audience.

"When the ONCE festival played 'Music for Clocks,' it got a good ovation," Krumm says. "[Experimental composer] David Tudor grabbed me and hugged me and swung me around. David Tudor! He was one of my superheroes. To have one of your superheroes do that? Fuck yeah!"

New World Records released Music from the ONCE Festival, 1961-66 as a massive box set in 2003, and it included "Music for Clocks." Krumm's piece received particular attention fromVillage Voice critic Kyle Gann.

"The most fun piece and the only one to slightly foreshadow the minimalism that was soon to break, is Music for Clocks, by Texan Philip Krumm," Gann wrote.

Sharing stages

By 1962, Krumm had entered the world of his heroes, among them Robert Ashley and John Cage.

"It helped that I was cute," Krumm says with a chuckle.

These heroes also included La Monte Young, whom Brian Eno later called 'the grandaddy of us all.'

"The time I met La Monte, he was in the bathtub," Krumm says. "Very funny man. Wonderful and strange. He was just ... sitting in the bathtub."

Young was a pioneer of Fluxus, which Dutch critic Harry Ruhé called "the most radical and experimental art movement of the '60s." Its interdisciplinary community spread internationally, and creators used it as an opportunity to create experimental works that placed the artistic process ahead of the finished product.

Young's piece "921," for example, consisted of the composer banging a kitchen pot 921 times.

"To me, that was one of the best things I ever sat through," says Krumm, who witnessed a performance of "921" at ONCE Fest.

Krumm also made early contributions to the movement. Some of his works were showcased in the first Fluxus newsletter, and his composition "Patterns" was featured at the first public Fluxus festival in Wiesbaden, Germany. Eventually, Krumm's piece "List" — a list consisting solely of the word "list" repeated over and over — was included in the Fluxus Codex, a definitive 1988 tome chronicling the movement.

Thanks to a connection with La Monte Young's girlfriend, poet Diane Wakoski, Krumm performed at Carnegie Hall with Yoko Ono, one of Fluxus' highest-profile provocateurs. Also on stage was George Brecht, a seminal Fluxus artist whose compositions Krumm had included in his early SA concerts.

"Yoko sat on a toilet in the front of the stage, reading her poetry," says Krumm of the performance, now considered legendary in new music circles. "Her boyfriend Tony Cox had a microphone backstage by the toilet and, every now and then after Yoko said something, there'd be this monster toilet flush coming through these big speakers. And within that framework was George Brecht, me and Terry Jennings, a great sax player, doing vocables — mouth sounds — with cans tied around our ankles, walking in a circle. It was good avant garde for its time. Good and proper avant garde."

That same weekend, Krumm made a pilgrimage to the Stony Point, New York home of John Cage, where they shared spiked dandelion tea and Cage's favored Gauloises cigarettes. In the back of Cage's station wagon sat an unopened box of his recently published book Silence, one of the seminal texts of experimental music. Cage gifted Krumm a copy.

"I got copy No. 1. Copy No. 1!" says Krumm, his disbelief persisting to this day.

When Krumm asked Cage to write a dedication in the book, Cage doubled over with laughter.

"'Write in the book?' he asked. 'I just wrote the whole book!'" Krumm remembers. "He really was one of the funniest people in the world ... one of the great people of the time."

At the 1963 Pataphysics Festival, organized by author Roger Shattuck, Krumm met Jerry Hunt, a lifelong friend and avant-garde luminary who later released Krumm's hauntingly beautiful "Sound Machine" on his Texas Music compilation.

The pair also hosted The Music Hour, a 1964 program on Austin's public TV station, performing John Cage scores with Ed Vizard, saxophonist for Asleep at the Wheel. Another TV performance from that time, "Sampler," linked Krumm with Waco native Robert Wilson, who later became an art world superstar with Einstein on the Beach, his operatic collaboration with minimalist composer Philip Glass.

Back to Texas

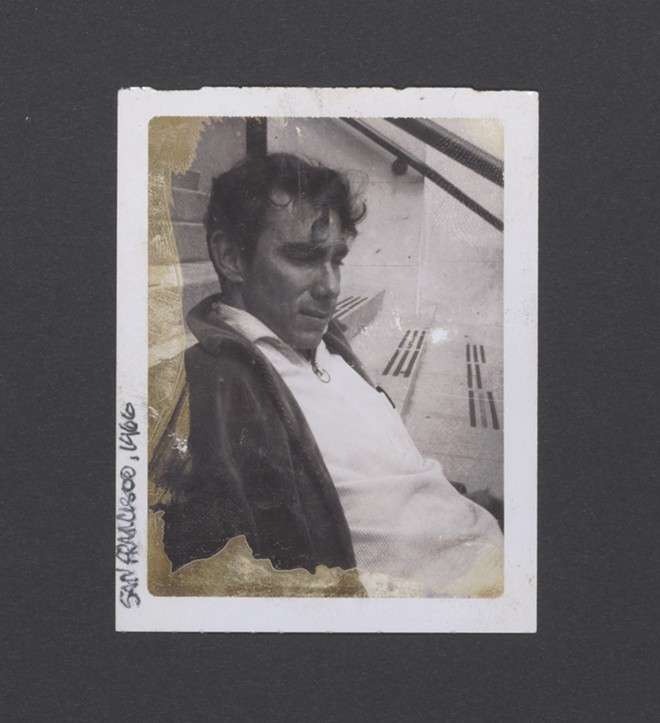

In summer 1966, Krumm headed to the University of California at Davis to work with yet another giant of experimental music, Karlheinz Stockhausen, whose tape loop experiments were the primary inspiration for The Beatles' "Tomorrow Never Knows."

However, this time, Krumm's great leap fell short: the school had no funding available for him. Krumm stayed in Davis for six months, auditing Stockhausen's classes, recording his composition "Sound Machine" and performing a well-reviewed concert with future new-age great and Brian Eno collaborator Harold Budd.

"Stockhausen was a bright spot in a difficult time for me," Krumm told Austin musician and writer Josh Ronsen in 2009. "He took a liking to me ... and invited me to have lunch with him ... . I saw him in concert a few years later ... . I went to talk to him after the concert, told him that I'd driven up from San Antonio to see him. He grasped my hand warmly and said, 'You are an angel!'"

While at UC Davis, Krumm worked the school's Buchla synthesizer, one of the first modular versions of the instrument, and made a little money composing music for Volkswagen commercials. Even so, he couldn't sustain life in California. To save money and care for his parents, he permanently moved back to San Antonio.

After his return, Krumm took an unlikely musical detour by participating — for a paycheck — in Truth of Truths, a Christian rock cantata staged by then-Trinity Baptist Church Pastor Buckner Fanning. Krumm, no big fan of religion, played synthesizer.

"All I had to do was play a little electronic sound behind God's voice now and then," Krumm said in 2009.

Fanning, of course, portrayed God.

Psychedelic pioneer

By this time the psychedelic '60s were in full blossom, and Krumm's artistic wanderlust led him into that nascent scene. Before long, he'd founded San Antonio's first light-show company, Light Sound Development — which boasted the apt acronym of LSD — with local visionary Charles Winans.

"He was one of SA's native geniuses," says Krumm of Winans. "One of the original avant-garde artists here in town."

LSD provided visuals for the short-lived Mind's Eye, billed as the first psychedelic nightclub in the Southern United States.

The company also designed the lighting for Hemisfair '68's Youth Pavilion, sometimes called Project Y. Beyond that, Krumm also had a hand in programming music for the pavilion, bringing in a range of bands and composers, from the ONCE group to William Russo, a trombonist who pushed the boundaries of jazz by combining it with classical music.

Eventually, Krumm also ended up managing two of San Antonio's most promising psych bands, The Children and Rachel's Children. Both bands played the opening of The Mind's Eye, alongside Texas' now-legendary and always mind-expanding 13th Floor Elevators.

"They were already named when I found them," Krumm says of his time shepherding the two musical groups. "'Manager' in quotation marks. I didn't know what I was doing, but they tolerated me."

Although Krumm didn't fancy himself much of a rock-band manager, he fully embraced the mind-expanding side of the era's music scene.

"I loved acid. Loved it," he says. "I had a lot at the appropriate time, back in the '60s, when it was the good stuff. I learned all my psychic lessons and had great respect for it. It never hurt me ... . It was never anything but nice to me. No matter the environment, a bunch of wonderful people or a bunch of monkeys — it always pulled me together. That was the initial effect I got from it — togetherness. It said 'you're very sane. Don't worry about it.'"

Meanwhile, Krumm's apartment — known as The Bug House due to its location above ABC Pest Control — emerged as a meeting place for the local counterculture. Cassell Webb, who sang for The Children, has fond memories of the place.

"The first time I met Allen Ginsberg was at the Bug House," she says. "Met Ginsberg and Bill Burroughs when they were coming through to have a good time in Mexico."

Sailing on

In the late '70s, violinist Jane Henry connected with Krumm, who invited her to join CAPASA, a composers group he led with the late San Antonio composer Sarmod Brody. Brody, who led Trinity University's music department, was a tireless advocate for adventurous music.

"At that time, Phil and Sarmod were cheerleaders," Henry says. "Connecting people. Very encouraging."

After meeting Krumm, Henry began hanging out at Clipper Ship, Krumm's nascent bookstore. It served as a connection point for the city's boundary-pushing creatives.

"Phil has always had salons," Henry says. "And Clipper Ship was the hottest bookstore in Texas — pun intended. No air conditioning. Probably never paid a utility bill. But it was wonderful."

Launched as chain booksellers were consolidating the retail landscape, Clipper Ship stood apart by refusing to carry Harlequin romances, bestsellers or anything remotely mainstream. It emerged as a hub of the city's literary scene, hosting readings from award-winning writer and filmmaker John Phillip Santos, 2000 Texas Poet Laureate James Hoggard, celebrated Chicana poet Lorna Dee Cervantes and Charles Behlen — one of Krumm's favorite poets — among many others.

Clipper Ship finally earned Krumm positive local press.

"Philip Krumm's bookstore is, for some, the last bastion of quality literature," Express-News scribe Ed Conroy wrote in 1987. "The entire Clipper Ship operation is a continuation of Krumm's campaign for contemporary arts in San Antonio."

The effusive 1987 article was a stunning reversal of the snidely dismissive reviews Krumm received for his early concerts.

Patchy legacy

After an extended run, Clipper Ship closed its doors in the early '90s. Krumm subsequently became a music critic at the San Antonio Light, which shut down in 1993, and a DJ at classical music station KPAC-FM, where his adventurous Musica Nova program won two awards from the Texas Music Association.

Sadly, though, his original music has nearly faded into obscurity, with the only recent release being his exceptional composition Formations — a piece written using star charts and performed by longtime collaborator Tyranny. It was released by San Antonio-based Idea Records in 2003.

However, after years of frustrating setbacks, Krumm was finally reintroduced on a national level with the aforementioned ONCE box set. His inclusion in Blank Forms' Jerry Hunt retrospective, its accompanying book released this year by the prestigious Blank Forms publishing house, may encourage further exploration.

Also, Krumm has finally released new music, Goofy Tunes and Minimalist Melodies, a delightfully bizarre home recording featuring extensive keyboard programming.

"I wasn't trying to do what I did before," Krumm says. "Just seeing what I could do with existing systems. I was happy with how it turned out, although it might be kind of amateur-ish."

So, why does such a groundbreaking artist linger in near obscurity?

In part, it could come down to a lack of accessibility. Many of his early scores were one-offs with no copies made. But observers say Krumm's confrontational approach also plays a part. His willingness to challenge conventional thinking wasn't always popular in Texas — and still isn't.

"As Texas is wont to do, it eradicates any history it deems unpleasant or unsightly," critic Beta explains. "Growing up in Texas, you can't help but fall victim to that cultural amnesia. Perhaps that's why a figure like Phil gets erased."

But Krumm isn't dwelling on his lack of recognition.

"San Antonio has certainly had more art and music people in it," he says with a grin. "But it's a little quiet right now."

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter