There's a distinct sense of mystery to Miraflores, the gated green space viewable from Hildebrand Avenue near Broadway.

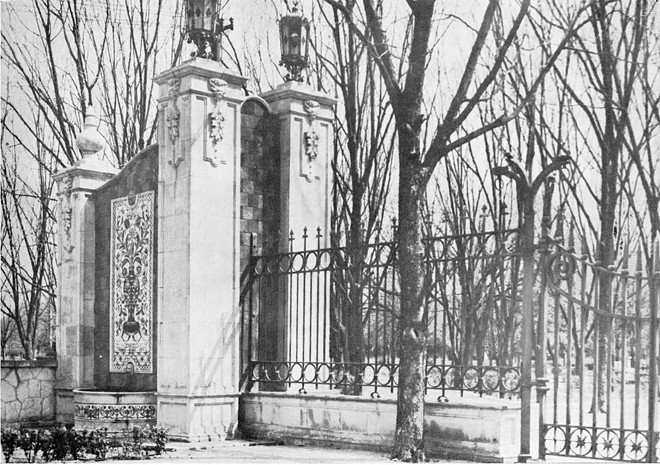

Evocative of Frances Hodgson Burnett's early 20th-century novel The Secret Garden, Miraflores invites imaginative speculation and has unwittingly welcomed countless trespassers. Many San Antonians who have driven past its ornate gates — which seemingly lead nowhere — have wondered what it is.

But the bigger question lies in what it was.

Writer Anne Elise Urrutia answers that in depth in her new Trinity University Press book Miraflores: San Antonio's Mexican Garden of Memory. A labor of love six years in the making, it employs archival photographs, maps, diagrams and a research-driven narrative to offer a virtual tour of the enigmatic landmark her great-grandfather Aureliano Urrutia began creating in 1921.

Born in 1872 in the Mexico City suburb of Xochimilco — a World Heritage Site famed for its picturesque canals and "floating gardens" — Aureliano Urrutia grew up with modest means during the Porfirio Díaz era and benefited from the president's education initiatives.

"Education started to become more available to people of the lower income classes," Anne Elise Urrutia explained during a recent interview with the Current. "He wound up getting promoted into a very prestigious high school in the center of Mexico City. He was at the top of his high school class. ... And Porfirio Díaz sponsored his medical education through his entry into the army."

During his two-year stint in the army, Aureliano Urrutia caught the attention of Victoriano Huerta, a rising army colonel who became a general and eventually the dictatorial president of Mexico.

By the turn of the century, Aureliano Urrutia had emerged as one of Mexico's premier surgeons. Opened in 1911, his 25-acre hospital complex Sanatorio Urrutia was surrounded by gardens, walking paths and outdoor sculptures. As Anne Elise Urrutia recounts in her book, Sanatorio Urrutia was also a cultural salon of sorts, where her great-grandfather's friends and colleagues — "influential writers, historians, musicians, lawyers, artists, and doctors" — gathered for intellectual discourse.

Amid the turmoil of the Mexican Revolution, Aureliano Urrutia was appointed secretary of the interior — a brief but fateful position that made him a scapegoat for the atrocities of Victoriano Huerta's rule and eventually led him to flee Mexico in 1914.

"His escape from Mexico was essentially sponsored by the United States government," Anne Elise Urrutia explained. "He fled Mexico City and went to Veracruz with six or seven members of his family, [all] disguised as peasants. They were intercepted by the United States government and were given passage on a military ship — the only passengers on a military freight ship to Galveston."

Sanctuary in San Antonio

Upon settling in San Antonio, Aureliano Urrutia bought two properties on what would later become Broadway — one for his medical practice, the other for a mansion to house his family of 13. When his wife Luz Fernández de Urrutia died in 1921, he purchased the tract that would become Miraflores.

Loss — of his wife, his homeland, his culture — essentially fueled the creation of Miraflores. An avid gardener and art collector, the successful surgeon began filling his nascent garden with plants native to Mexico and commissioning Mexican artists to create monumental outdoor works.

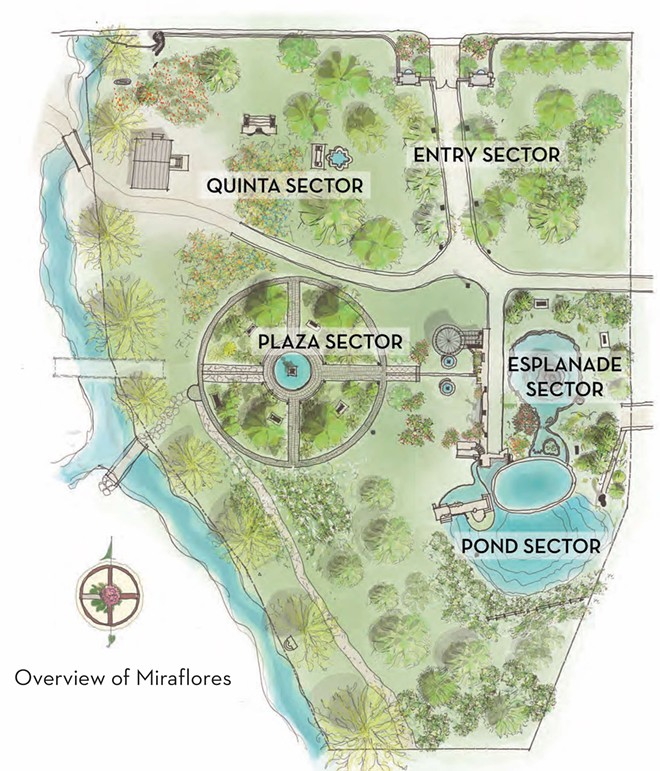

Beginning with Luis L. Sanchez's 1921 statue of the Aztec ruler Cuauhtémoc, the sprawling outdoor collection at Miraflores grew to include staircases, gates, bridges and a volcanic-style fountain by trabajo rústico pioneer Dionicio Rodríguez, a bust of Porfirio Díaz and elaborate benches adorned with illustrative Talavera tile.

Perhaps the most recognized elements of Miraflores, the imposing gate "Monumento a la Ciudad de México" still stands guard on Hildebrand while the massive, tile-covered Urrutia Arch now resides at the San Antonio Museum of Art.

Full-scale buildings were constructed on the property as well, including a quaint country house dubbed Quinta Maria and a three-story watchtower with a conical roof, blue-and-white tile detail and a bell. Located near the source of the San Antonio River, Miraflores sits atop underground springs and once boasted natural ponds. In homage to his roots along the canals of Xochimilco, Aureliano Urrutia celebrated these natural water features and commissioned a bridge that stretched across a pond and doubled as a stage for live entertainment.

In its prime, Miraflores functioned as a sanctuary for quiet contemplation, a destination for meetings of the minds and a venue for special events ranging from chamber concerts and fundraisers to private parties.

In 1931, the garden welcomed the American Institute of Architects (AIA) for an "evening fiesta" complete with a flamenco performance on the stage bridge. Among the guests at that AIA event was architect Atlee Ayres, who was fascinated by Aureliano Urrutia's inventive use of Talavera tile throughout Miraflores.

During her extensive research, Anne Elise Urrutia dove deep into the history of Talavera.

"I learned a lot about the history of Talavera," she said. "It's definitely something that was brought by the Spanish colonists ... but it's also a craft that is indigenous to Puebla, Mexico. And the people of Puebla really embraced the making of Talavera tile."

While Miraflores shows Aureliano Urrutia to be an early champion of Talavera, Anne Elise Urrutia suspects he actually might have been the first person to bring it to the United States. At the very least, he was way ahead of the curve — as was architect Ayres, who helped embed Talavera tile into the cultural fabric of San Antonio through landmarks spanning from the McNay Art Museum and the Randolph Air Force Base Administration Building, also known as the Taj Mahal, to numerous residential projects.

Changing hands

In 1962, at the age of 90, Aureliano Urrutia sold Miraflores with a deed that stipulated it would be preserved as "a spot of beauty." As Anne Elise Urrutia details in her book's epilogue, that deed wasn't properly upheld by subsequent owners USAA (1962-1974), Southwestern Bell Telephone (1975-2000) or the University of the Incarnate Word (2000-2006).

"During USAA's ownership of Miraflores, the company encroached on the five-acre garden, converting it to expand their parking lot, and added a small building and a conventional rectangular swimming pool to the southwest quadrant as a recreational area for their employees' children," she writes.

Although Southwestern Bell claimed it would "continue the preservation" of Miraflores, it leased the property to the Telephone Pioneers of America, a volunteer group that proceeded to drain and fill in a large pond, cut down trees, destroy pathways and install a 4,000-square-foot pavilion flanked with barbecue pits and bathrooms. During this period, some of Miraflores' key objects began decaying — and even disappearing.

Within a year of taking ownership, UIW destroyed Dionicio Rodríguez's trabajo rústico fountain that once served as the joyous center of Miraflores.

"Not only did they take it apart, but the city came in and sealed the well that was powering that fountain," Anne Elise Urrutia pointed out during conversation. "That was an artesian well that was drilled 150 feet down."

The university attempted to relocate 14 works of public art and build a parking lot in the garden — both were unsuccessful — but managed to block a nomination that would have placed Miraflores on the National Register of Historic Places.

Uncertain future

Owned by the City of San Antonio since 2006, Miraflores is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is designated as a State Archaeological Landmark by the Texas Historical Commission. In 2019, the nonprofit Brackenridge Park Conservancy signed a 10-year agreement with the city to manage Miraflores, then commissioned a cultural landscape report that indicates it has "great potential as a restoration candidate."

During our chat with Anne Elise Urrutia, we asked the author what an ideal restoration might look like to her.

"It's a good question," she replied. "I worry a little bit about what might happen in a restoration. I think there's a tendency to sanitize things when they get restored. And there are a lot of different interests at work. ... Miraflores is now part of Brackenridge Park, and it belongs to the city — so the garden belongs to the public, to the people. How is that going to be incorporated into a restoration? Will there be access hours? Will there be security? Will there be maintenance? How are they going to reinstate waterways that were once there? There are huge logistics in terms of any sort of restoration. That said, on the other hand, you have a park like Central Park in New York City, which was a huge mess in the early 1980s. And they got it together and restored that park largely. ... So, it's not that it's not doable. But the question is really, is it doable in San Antonio at this time? Is there the will to do it? ... I don't see it immediately."

Will aside, funding is a sizable factor.

"I can pretty safely say that there is no money set aside for the overall restoration of Miraflores," she added.

Although Anne Elise Urrutia hopes her book will generate interest in a thoughtful and comprehensive restoration of Miraflores, she also wrote it as a living record of sorts.

"What I really wanted to do was show what Miraflores was at the time," she said. "Basically to recreate it in a book just in case it never gets restored."

Stay on top of San Antonio news and views. Sign up for our Weekly Headlines Newsletter.