Editor's Note: CityScrapes is a column of opinion and analysis.

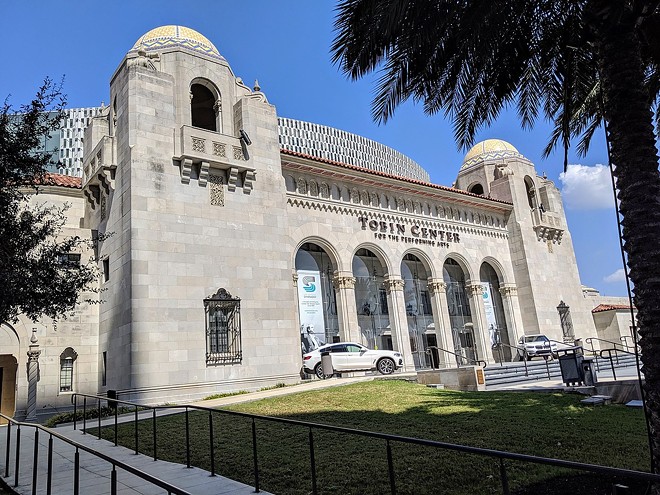

"Let the oohs and ahhs begin." So began Hector Saldaña's September 5, 2014, Express-News story on the grand opening of the Tobin Center for the Performing Arts, the "new home of San Antonio's symphony, opera and ballet companies."

The center, completed at a cost of over $200 million, with much of that total coming from a "venue tax" imposed by Bexar County, opened to an enthusiastic chorus of superlatives from both music lovers and local officials.

"Just the electricity walking in," County Judge Nelson Wolff offered. "It's unbelievable."

But the real promise from the remake of the city's Municipal Auditorium was that it had the capacity to transform the local cultural landscape and the city's larger economy. For former Mayor Phil Hardberger, there was the promise of luring new business to San Antonio. He contended that a big reason for building the Tobin Center in the first place was to give the city another selling point for employers looking to relocate by boosting the local quality of life.

Sebastian Lang-Lessing, the symphony's music director at the time, saw the new structure as a means to drive more recognition for the arts organization.

"I knew with the Tobin Center, I could move the orchestra on a different level of recognition and of performance, which is important," he said. "And I also knew that despite all the troubles that the orchestra landscape has at the moment when it comes to financing, this has the impact of boosting our recognition, our donor base and our capacity to be recognized in the community and outside, even."

So here we are now, in 2022, eight years after that grand opening. The San Antonio Symphony is gone, together with Sebastian Lang-Lessing. Somehow, this community could manage to build a grand new performing arts center, and yet fail to support and sustain a symphony orchestra originally founded in 1939.

Despite all the glitter of the Tobin, all the recitations of San Antonio being the "seventh largest city" and all the new population and development the city and county have witnessed in recent years, the San Antonio Symphony limped from one financial crisis to another.

Some symphonic music will no doubt continue under the aegis of the new San Antonio Philharmonic — although, at least for now, not at the Tobin. Of course, the Tobin's other two "resident companies," Ballet San Antonio and Opera San Antonio, are still using the facility. Yet it's far from evident that those organizations have prospered in their new home. Ballet San Antonio's 2022-23 season schedule shows three productions, including the perennial Nutcracker, while Opera San Antonio will put on Pagliacci in November and Romeo and Juliet in the spring.

Then there is the similar tale of the Museo Alameda in Market Square. Boosted by funding from the Ford Motor Company and the promise of being the first Smithsonian Institution affiliate museum in the nation — one with a unique focus on Latino art and culture — the Museo opened to great fanfare in the spring of 2007, even garnering a review in the New York Times, though the one element of the museum that warranted praise in that piece was the gift shop.

City leaders promised that the new museum would attract 400,000 visitors a year. But it was soon evident that without its own collection and funding, not to mention a clear vision or direction, the museum was failing both as a cultural addition and a visitor draw. The city and county governments and Texas A&M-San Antonio made attempts to jumpstart the space. It now sits as the underused, city-owned Centro des Artes gallery.

In the annals of failed grand projects here, few can surpass Hemisfair. The folklore is that the development of the fair in 1968 boosted San Antonio into international prominence and secured our place as a great tourist destination. But once the fair was over, failing to reach its projected attendance and out of money, there was nothing left over to turn many of its leftover structures and facilities — from the skyride and mini-monorail to the waterskiing lake and pavilions — into something useful and valuable.

In the mid-1980s, the city finally got around to demolishing much of the fair's remnants, turning the fairgrounds into a park. Yet only recently has the Hemisfair Park Redevelopment Corp. managed to make the fair site into a truly functional public and private space.

Why does San Antonio appear to be so good at building civic buildings, yet so manifestly poor at supporting their use and sustaining the arts and culture? In part, it's because we remain a relatively poor city, despite all our growth. There's a razor-thin stratum of wealthy, potential donors, both individual and corporate. And they appear far more interested in putting their names on buildings than in supporting artistic performance.

But perhaps the most important reason is that this remains a city whose big decisions are fundamentally driven by land and development deals.

So, while local grandees like County Judge Wolff celebrated the wonders of the newly opened Tobin Center, the most telling assessment came from Pat DiGiovanni, the long-departed assistant city manager and former head of Centro San Antonio. He said the Tobin "should be a magnet for continued revitalization. ... Part of the strategy for a revitalized downtown is enhancing the cultural aspect of our community."

We can still hope to enhance that cultural aspect.

Heywood Sanders is a professor of public policy at the University of Texas at San Antonio.

Stay on top of San Antonio news and views. Sign up for our Weekly Headlines Newsletter.