As San Antonio embarks upon yet another reimagining of downtown's Hemisfair, it's worth remembering the origin of the downtown space that includes the Tower of the Americas and other landmarks.

The development arose out of the controversial and city-altering Hemisfair '68, San Antonio's World's Fair and, in many ways, our introduction to the larger world. While Hemisfair was viewed as a win for the city's business establishment, a now-forgotten pavilion operating under the World's Fair banner that was anything but establishment — especially for the time.

Project Y, also known as the Youth Pavilion, became a forum for the most radical, entertaining and revolutionary ideas of the 1960s — from progressive pedagogy and public debate forums to psychedelic light shows and Fluxus-style happenings. Miraculously, the ideas came to fruition without the conservative city establishment swooping in to shut them down.

"Every once in a while, you do something and you don't know how," Philip Krumm, one of Project Y's music producers, said of the pavilion. "That's what that was."

Inspired by Trinity University drama professor Paul Baker and led by a visionary team consisting of urban planner and author Sherry Wagner, progressive educator Jearnine Wagner and transplanted New Yorker David Bowen, Project Y tapped into the late '60s' revolutionary spirit.

After landing a U.S. Department of Education grant, Project Y took on a life of its own. Rather than a prescribed experience mandated by a hierarchical authority, it became something more akin to a "happening" or an experimental theater project.

"PROJECT Y at HemisFair '68 is not an exhibit, but an environment for activity," read the original promotional materials. "The key ingredient is the creative energies of those who come to it."

Project Y's young staff, which included celebrated historian Lonn Taylor, multimedia composer George Cisneros and avant-garde composer Krumm, provided much of that creative energy. For those lucky enough to experience it, Project Y encapsulated the magic of the era — optimism, radical experimentation and youthful energy. All backed with an actual budget to realize the lofty ideas.

Sited on a 113,000-square-foot plot adjacent to the Institute of Texan Cultures, Project Y consisted of a theater-cinema, a cabaret, an outdoor discussion pit, areas for painting and a central plaza. Paraphernalia — the legendary NYC boutique that hosted Andy Warhol's exhibitions and performances by the Velvet Underground — even had a branch inside.

During Hemisfair's six-month run, national politicians spoke in the open air forum and experimental films played in the cinema. Music blasted from the cabaret, which hosted acts ranging from psychedelic visionaries the Electric Prunes performing their Mass in F Minor concept album to groundbreaking composer Robert Ashley's ONCE group.

Project Y also hosted the Genesis Fest, billed as the first pop-rock festival in the American South. Organizers fresh from the Monterey International Pop Festival produced the event, which reportedly featured a spectacular light show and performances from a broad range of Texas greats. Country-blues guitarist Mance Lipscomb and Alamo City street performer Bongo Joe played, and so did now-legendary psych acts including Bubble Puppy, Sweet Smoke and The Children.

Despite the pavilion's breadth and ambition, there's scant documentation of its freewheeling wonders.

"Unfortunately, there are few known photos of Project Y," said Tom Shelton, photography curator for the University of Texas at San Antonio's Special Collections library and home of the official Hemisfair archive. "This was an interesting and mostly forgotten area at Hemisfair. It's a shame more photos aren't available."

Dubious origins

The selection of the Hemisfair site, developed over the Germantown and St. Michael's neighborhoods, was mired in controversy from the beginning. Under the dubious claim of "urban blight," the city razed the neighborhoods for the fair, displacing 2,239 residences and 636 businesses, according to records. Workers demolished more than 1,300 structures and altered or erased some two dozen streets.

Just as the experimentation of Project Y represented one side of the '60s, the remaking of Germantown and St. Michael's represented a far less enlightened side of the decade. Cities across the country undertook similar projects under claims they were rejuvenating their city centers.

"Urban renewal ... means Negro removal," author James Baldwin famously quipped.

"Hemisfair was a very controversial thing from the first," said composer and Project Y participant Cisneros, who now runs urban dance group Urban-15. "It took two of the oldest and most important neighborhoods in town and, using eminent domain, ripped them apart."

Famed architect O'Neil Ford, Hemisfair's chief designer, sought to preserve the area's most historic and architecturally significant homes, but in the end, only 22 of the 300 historic homes were spared, mostly due to the San Antonio Conservation Society and liberal Texas Sen. Ralph Yarborough.

Ford resigned in protest, only to be replaced by Allison Peery, one of his disciples.

Big ideas and grants

Ironically, it was Peery's involvement in Hemisfair that helped usher in Project Y. During the planning stage, the architect wanted a youth area where parents could drop off their children.

"Somewhere between daycare and art camp," Cisneros explained.

Taking the helm of this fledgling youth program was Sherry Kafka Wagner, later a founding editor of Texas Monthly and an urban planner who helped create the San Antonio River Corridor, the San Antonio Missions National Historical Park and major projects from Boston to Kuwait.

"I'd never been to San Antonio, never thought about San Antonio," recalls Wagner, who at that time was divorcing her first husband, former Alamo City mayor Phil Hardberger.

She became the only woman to land an executive position at Hemisfair executive position after winning over fair bigwigs Bill Sinkin and Alison and Mimi Peery with a speech on childhood creativity.

"I had set up a program for children at the Methodist Children's home in Waco, so I was very interested in inherent creativity as a basic scaffolding of the mind," Wagner said. "The basic way the mind works. All learning is sensory. The creative process is the basic learning process. It's the cake, not the icing on the cake."

Wagner's revolutionary approach to learning had itself been learned from Paul Baker, an influential educator and theater director, whom the Texas Cultural Trust once called "the most important man in the history of Texas theater."

Inspired by cubist painting and its simultaneous depiction of multiple perspectives, Baker built Studio One at Baylor University, one of the nation's first truly experimental theater companies. Instead of a single proscenium stage, six stages surrounded members of the audience, who were seated in swivel chairs to rotate their view between stages.

Baker's theater program became a media sensation, winning praise from Life Magazine and major TV networks. He later collaborated with Frank Lloyd Wright on the similarly designed Dallas Theater Center, which actor Charlton Heston labeled "the greatest theater in the world."

A controversial production of Eugene O'Neill's Long Day's Journey into Night led to a protest campaign by a Baptist Sunday School teacher. Rather than be censored, Baker migrated the entire Baylor theater department to San Antonio, where he became head of Trinity University's program and oversaw construction of the Ruth Taylor Theater, which also featured multiple stages and swivel seating — which have long since been torn out.

Among those who joined Baker in his move to Trinity was protege Jearnine Wagner, who'd started Trinity's Ideas in Motion children's program and written the workbook Our Theater: A Place for Ideas with Baker's wife Kitty. Back at Baylor, Jearnine Wagner had helmed the children's theater with Project Y head Sherry Kafka Wagner — no relation — and was thus a natural recruit for Hemisfair's Youth Pavilion. Fueled by Dr. Pepper and Hershey's bars, the pair applied for, and won, a $470,000 US Department of Education grant to expand the pavilion from the "daycare" Peery envisioned into something truly transformational.

Students and issues

Using the funds, the pair initiated Unlimited Potential, a San Antonio Independent School District program that emphasized learning through creativity, especially for low income students. In conjunction with Paul Kantz, a new SAISD assistant superintendent, Unlimited Potential — and its new homebase at Project Y — sought a fresh, inclusive approach in a broken, racist educational system.

"In those days, if a child was caught speaking Spanish on the playground, he was expelled for three days!" Sherry Wagner said of the backward learning system of the day.

Unlimited Potential arranged for students from the city's poorest districts to experience World's Fair and specifically Project Y. The pavilion was staffed largely from Baker's Trinity theater department and with students and faculty from elite high schools. The mingling between the city's richest and poorest schools provided a unique opportunity.

"Paul saw this as an opportunity to take his Trinity students in theater art and music and visual arts and put them in a community context where they could provide an enlightened experience. It was an eye-opening experience for everybody," Cisneros said. "People from Alamo Heights and Trinity for the first time saw San Antonio in a different way, because they were downtown. And people from the rest of San Antonio got access to the rarefied Alamo Heights-Trinity world."

With Project Y off the ground, Sherry Wagner hired Bowen, a bilingual children's author and educator, to helm Project Y. For the duration of the fair, Sherry Wagner focused her energy on the Women's Pavilion, the fair's only self-funded pavilion and a refreshing feminist presence in the repressive patriarchy of mid-20th century Texas.

As Hemisfair unfolded, turmoil gripped the nation. The Vietnam War raged, the civil rights movement reached its height, college campuses emerged as hotbeds of dissent.

"So, we decided to have a Hall of Issues," said Israel Anderson, who worked on Project Y as a recent college grad. "And inside that Hall of Issues, we imagined kids having small group discussions. A place where kids could talk about all the current issues of the day. Like a Roman forum."

Painter and activist Phyllis Yampolsky conceived of such forums a few years prior while working for the New York Parks Department to coordinate "happenings," a term coined by Fluxus artist Alan Kaprow. The concept dovetailed with the spirit of Baker's revolutionary theatrical approach.

Project Y's organizers brought in Yampolsky as a consultant to help recreate her own Hall of Issues, an open-call exhibition and program series held at New York's Judson Church, now considered an iconic moment in that city's revolutionary '60s art scene.

"Project Y is really a series of constantly changing events that occur because people are present ... not an exhibit, but an environment for activity," the pavilion's promotional materials explained. "The key ingredient is the creative energies of those who come to it. It is a showcase for creative energies in industry and the professions, and for those taking shape in churches, neighborhood houses, universities and — like a flower in a rock — in the streets of our cities."

Recent Trinity graduate Anderson, an African American, landed the job of overseeing the Hall of Issues. His deep commitment to social justice and civil rights led him to Trinity's urban studies master's program.

"I was a 21-year-old kid of the '60s, grew up in the segregated public school system in Waco," said Anderson, who moved to San Antonio to take part in Trinity's master's program in urban studies. "To go from there to Trinity University was like walking on another planet."

While the Alamo City was more open than Waco, it was still a different time — as Anderson learned when he walked from Trinity to Olmos Pharmacy for a haircut.

"Head barber asked me, 'Can I help you?' I said, 'I came in to get a haircut.' He said, 'You'll be the first Black guy to get a cut in here. All the Black folks go to the East Side.'" Anderson remembered. "So, I walked from Hildebrand [Avenue] to New Braunfels [Avenue] ... . Crossed over the bridge there and was immediately in Black town. All the barber shops, beauty shops, cafes — all Black."

After his graduation, Jearnine Wagner recruited Anderson for Project Y and he seized the opportunity, writing hundreds of letters to heads of state, thinkers, authors and diplomats urging them to speak at Project Y. Among his major catches: Robert C. Weaver, President Lyndon Baines Johnson's secretary of housing and urban development and the first Black member of any White House cabinet.

"I also brought Boris Davydov, the Soviet ambassador from D.C., and that caused quite a stir," Anderson said. "I know the FBI was following him everywhere."

Innovation and LSD

Cisneros credits his involvement in Project Y for helping him launch Urban-15, its Third Coast New Music Series and other ambitious creative and educational programs that have left a significant impact on the city.

"I can draw a line from so much of my life that started at Project Y," he said.

His involvement at Hemisfair began as part of The Octet, a hootenanny folk group he described as a "thing for the tourists."

"We'd wander around the fairgrounds performing, but in between sets, there was all this work to be done, and I went over to Project Y, where there were interesting things happening," he said. "Before too long, they realized, 'This guy knows how to do work.' I ended up being their AV guy."

Cisneros was hurled into the deep end, running multiple productions simultaneously. Aside from the hands-on technical knowledge he gained, Hemisfair exposed Cisneros to new technologies at the ITT and Bell Labs exhibits, where he saw his first video phone and modular synthesizer.

"Everything I've worked on my whole life, it all percolated up from that time," he said.

Legendary San Antonio composer, bookstore owner and cultural provocateur Philip Krumm — recently profiled in the Current's March 8 cover story — was among the other creatives drawn into Project Y's orbit.

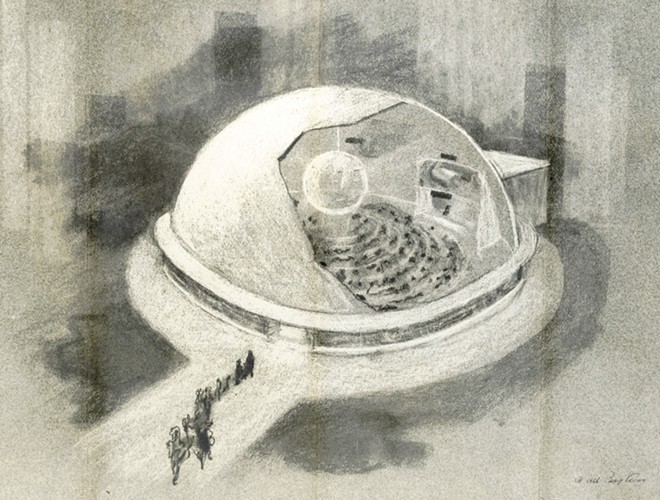

Having already gained local notoriety, he proposed an ambitious dome concert hall he termed the Total Experience Theater, an immersive environment reminiscent of designs by experimental music legend Iannis Xenakis. In the end, those controlling Hemisfair's purse strings declined to pursue Krumm's grant vision.

"We didn't get that, but we did get a round building," he said.

Krumm ended up as a music programmer for the pavilion, while also running its light show with his company Lighting Sound Development, or LSD. Founded with San Antonio visual artist Charles Winans, LSD had already provided visuals at short-lived music venue The Mind's Eye, considered the South's first psychedelic music club.

At Project Y, the pair delivered their trippy visuals via a custom-built turntable filled with mirrors, lenses and bits of colored glass — a technique gleaned from Milton Cohen's Space Theater.

"The light show was fantastic," Krumm said. "One of the best things I've ever done."

Genesis Fest

Pop-rock festivals thrived in 1968, and Project Y had its own.

Legendary Houston venue Love Street Light Circus, Austin's Vulcan Gas Co. and San Antonio's Alamo Electronics joined forces to present Genesis Fest, an event billed as the South's first pop-rock festival.

The concert's technical directors, led by Gregor Gregg, arrived directly from the famed Monterey Pop Fest, where they'd achieved considerable success launching the careers of iconic performers including Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Otis Redding.

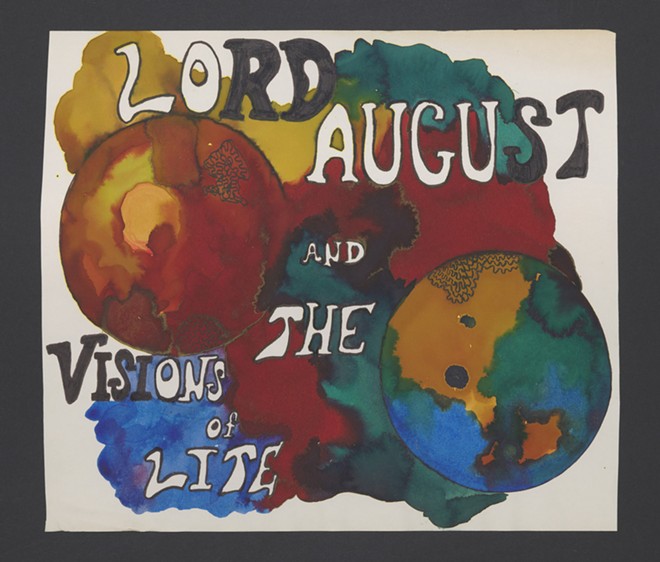

While Genesis Fest didn't prove to be a launch pad for talent of that level, it still tallied 18,000 attendees, according to organizers. In addition to the aforementioned Bubble Puppy and Bongo Joe, the lineup included Shiva's Headband and Augie Meyer's Lord August and the Visions of Lite. Even Gov. John Connally's son performed, with his questionably named group The Starvation Army.

Despite the tremendous turnout, Hemisfair management denied Project Y's request to fund a second music fest.

Also denied was the Youth Pavilion's request to bring in the un-Google-able United States of America, a dynamic LA group led by composer Joe Byrd, whose sole album for Columbia many critics consider a masterpiece of psychedelia. USA had been scheduled to perform at Project Y's opening celebration but H-E-B, a corporate sponsor needed to fund the group's fee and expenses, deemed the group "just not something we are interested in," Krumm recalled.

A significant Project Y performance — and one seemingly forgotten — was the ONCE group, led by groundbreaking composer Robert Ashley. Recruited by Krumm and theater coordinator Don Davlin, ONCE mounted a stunning three-day performance of That Morning Thing, Ashley's revolutionary work of light, sound and theater.

Upheaval and healing

On April 4, 1968, two days before Hemisfair's opening, James Earl Ray assassinated Martin Luther King Jr., shocking the entire country. Recent Trinity grad Anderson took the death especially hard.

"For a while there, I was despondent as hell," he said. "I took time off, went to D.C. — it looked like a bomb had gone off. The riots had occurred. Down on the Mall, Black Panthers and SDS, they'd created a poor people's city. 'Resurrection City' it was called. People camped in their tents. I went there and stayed four or five days."

After seeing a city in tatters, Anderson returned to San Antonio, pouring his energy into Project Y. He helped provide a setting for young people to process their emotions with theatrical demonstrations and a large wall to write their thoughts.

"After King's assassination, we dressed all the kids up, dressed in black, as mimes," he said. "They didn't talk. Silence. For that and the RFK assassination ... there was a lot of silence that year."

Music also played an integral role in the healing. For Hemisfair's opening and the first Project Y show, the city commissioned composer Bill Russo to write Civil War: A Rock Cantata. Although ostensibly about the U.S. Civil War, the piece felt especially resonant in the tumult of 1968.

As arranger for Stan Kenton's famed big band, a Duke Ellington collaborator and founder of the London Jazz Orchestra, among other things, Russo was already a major figure in music. His specially commissioned piece sought to blend the excitement of the rock scene with theater, classical arrangements and a modular score that allowed local musicians to perform with only one or two rehearsals.

Project Y's opening celebration also featured a 100-foot long loaf of bread, baked to order, and an experimental film by Saul Bass, the Oscar winner known for his visually arresting title sequences for films including The Man With the Golden Arm and North by Northwest.

The opening performance garnered ecstatic reviews. San Antonio Light music critic Don Gardner described Civil War Rock Cantata as "the most exciting single musical event I've ever witnessed."

Psych out

Krumm remembers it differently.

"We sat up all night before the show, with a bottle of [widely abused upper] dexamyl," Krumm said in a 2015 interview. "Smoking pot and drinking from the dexamyl bottle. It came time for the gig, and we were all pancake-brained. Everyone was burnt and our lips were all crusty ... . And there is a picture of me in the paper, and we're all baked, and I looked like a beatnik ... . It was so horrible. The singer forgot the words and scatted through it. I kept my flute down... But everyone loved it. It was done with slides of Mathew Brady's fabulous photographs of Civil War dead. It was a very beautiful visual and musical production. No one could tell I wasn't doing anything."

The band for Civil War Rock Cantata's performance was San Antonio-born psychedelic group The Children, who later repurposed some of the compositions for their sole album on Atlantic Records, Rebirth, now considered a lost classic.

"They recorded those songs without asking [Russo]," said Krumm, who managed The Children for a while. "Probably wasn't the right thing to do, but they were kids! And it didn't hurt anybody and got his stuff in front of new people — in front of a whole new crowd."

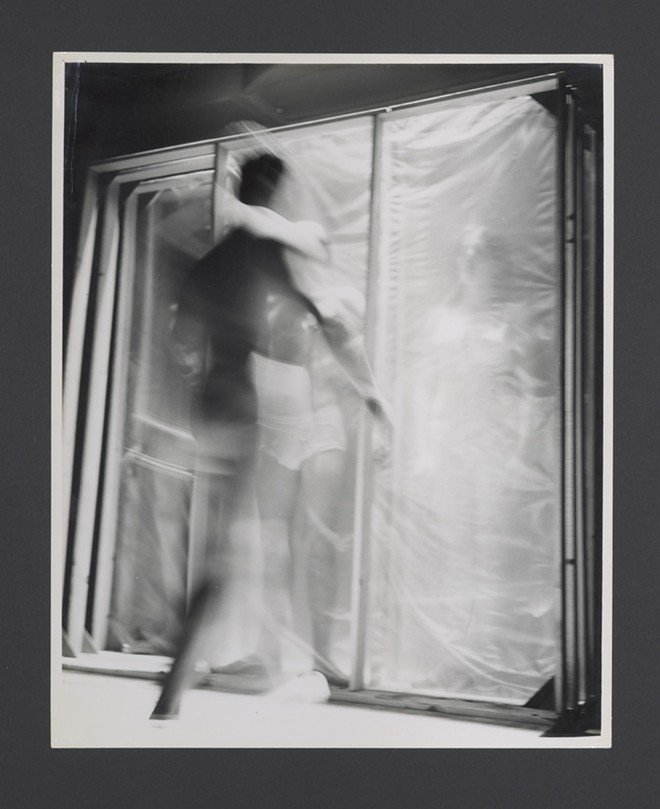

Another band Krumm managed, Rachel's Children, also put on a stunning performance at Project Y, with Krumm and light-show partner Winans employing eight overhead projectors, four film projectors, a stereo slide projector and other gear to provide mind-melting visuals.

"It became one of the most astonishing musical-techno-cultural alterations of collective reality where all the participants were, for a few minutes at least, totally united in a transformative experience," Krumm recounted in a 2009 interview. "When it ended, my Youth Pavilion supervisor looked at me with a dazed expression and said, 'That was the most amazing damn thing I've ever seen!'"

Sadly, no documentation of the show exists, and the band recorded an album, but the tapes ended up with Billy Brammer, best-selling author of The Gay Place, a fictionalized history of LBJ, and huge fan of the group.

"I'd met Bill Brammer while working at Hemisfair, where he was in some top-level position," Krumm said. "He claimed he was the only person he knew of over 50 still shooting speed. Three weeks or so later he was dead, and the tapes disappeared with him."

A different era

Clearly, Project Y's ambition and progressive edge reflected a different time in San Antonio, when the city was a hub for the burgeoning '60s youth culture. Folk venues such as The Ichthus gave voice to the anti-war movement, while teen clubs nurtured a vibrant garage rock scene. The neighborhoods were different too.

"King William was the Hippieville of San Antonio," Cisneros explained. "There'd be peace flags all in the windows of the big mansions. There'd be 20 people living in them. A lot of people whose families owned houses in King William. Amazing parties down there at that time."

As a result of the thriving clubs and hippie scene, numerous bands stopped in San Antonio, often performing informally at Project Y.

"People would pass through town, and we could do stuff just at Project Y, not through Hemisfair," Cisneros added. "A lot of after-hours stuff went on."

Among those acts was the 13th Floor Elevators, the Austin outfit considered the godfathers of Texas' psychedelic scene. One of those Hemisfair-adjacent gigs proved to be the setting for the group's demise.

After ingesting untold amounts of acid, Elevators frontman Roky Erickson was teetering on the edge of sanity. Krumm bumped into Erickson and a friend outside Love Street Light Circus, where the singer asked to borrow Krumm's 1966 Cadillac hearse. Not knowing the Elevators were scheduled to play Love Street that night, Krumm agreed.

"Only minutes later, [Elevators electric jug player] Tommy Hall showed up looking for Roky," Krumm said. "They were scheduled to perform ... and the manager was already in a bad mood and now Roky was obliviously headed for Austin in my hearse."

A row ensued, brought on by the abusive venue manager, according to Krumm. Shortly, the 13th Floor Elevators were no more.

"That was the end of their concert work together," he said.

Remembering Project Y

Hemisfair shut down in the fall of 1968 following its planned six-month run.

Texas historian and museum curator Lonn Taylor summed up the site's sense of promise during a 2018 speech. He recalled being drawn to Hemisfair as a young grad-school dropout, hoping to land a writing job that promised a $10,000 annual salary.

"I joined ... and for the first time in my life worked with architects and exhibit designers, people who turned ideas into three-dimensional environments," said Taylor who later went on to work for the Smithsonian Institution. "It was a transformative experience for me."

However, in this same address, Taylor minced no words about Hemisfair's aftermath. At one point, the site was slated to become the University of Texas at San Antonio campus, but the UT Board of Regents rejected the idea in favor of another location north of the city.

Taylor and others argue that the decision was guided by the fact that suburban site was adjacent to land owned by powerful interests including the La Ventura Corporation — owned by regent and San Antonio attorney John Peace, Gov. John Connally, San Antonio developer Charles Kuper and others.

"The most important planning decision in the history of San Antonio," said Taylor, "A decision that led directly to the city's suburban sprawl to the north and west rather than the development of a compact, mixed-use urban center around the river and the Hemisfair site, was made by a group of real estate developers motivated by private profit with absolutely no input from professional planners nor, indeed, anyone representing the interests of the city of San Antonio."

Taylor aptly summed it up: "Thank you, Hemisfair, for showing me what my life's work was intended to be, and shame on you, San Antonio, for allowing your future to be dictated by a group of land profiteers."

Cisneros concurs.

"What happened after Hemisfair is the real tragedy. It went derelict," he said. "It was frightening. The only ones loyal were the Mexican Cultural Institute and [Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico]."

Which brings us to the present day, where developers and the city are once again trying to breathe life into Hemisfair.

"The idea of it becoming a condominium-apartment-hotel environment is really a tragedy," Cisneros said. "The people whose land was taken, they weren't allowed to come back once it became domicile. That's a really heavy political admission you have to go through."

In spite of the pain surrounding Hemisfair's origin and conclusion, Project Y remains a golden memory to Cisneros and others involved.

"I see guys now that are bankers, founded industrial companies, but we see each other [now], and we're just, 'Remember that time when we couldn't walk home?" Cisneros said with a laugh.

In retrospect, Project Y's light and sound extravaganza, its multiple stages, visionary staff and innovative programming was San Antonio's own impressive version of the revolutionary "happenings" taking place in larger cities, even though it got considerably less attention and has been long since forgotten.

"People talk about some collective experience at those shows ... but there's no telling," Krumm said. "There were many alternate realities floating around! But that was the right time for it — it was hot times."

Subscribe to SA Current newsletters.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter| Or sign up for our RSS Feed