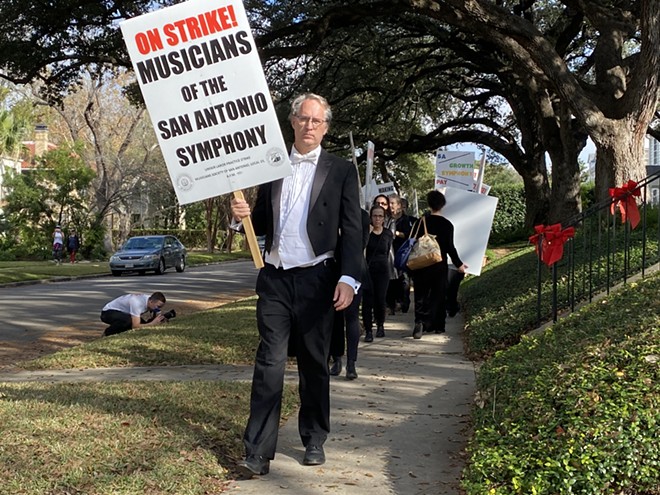

For both sides, the short-term effects of the strike are grave. Musicians have lost pay and benefits and face uncertain futures, while the symphony itself has lost credibility both with its employees and the broader community, observers note.

At stake isn’t just the question of whether San Antonio will continue to have a top-class professional orchestra but whether the city will lose musicians who comprise a key part of its creative community.

The last offer by the Symphony Society, the orchestra’s managing body, was to cut the number of full-time musicians in the financially strapped organization from 72 to 42, eliminating four positions and converting 26 more to part-time. The offer, made in late September, is one Trinity University assistant professor of music Joseph Kneer called “unheard of.”

Musicians of the San Antonio Symphony (MOSAS) chair Mary Ellen Goree said accepting such an offer would effectively end the symphony as we know it.

“The option is not between the full-time symphony and the smaller core,” Goree said. “The choice is between a full-time symphony and no orchestra at all.”

In such a scenario, many who won auditions for full-time jobs with the symphony would leave for work elsewhere, Goree cautioned. Musicians of similar caliber wouldn’t relocate to San Antonio to replace them — not for a position that doesn’t pay a living wage.

Dwindling staff, dwindling funds

Musicians blame inadequate fundraising for the current financial situation. Corey Cowart, executive director of the San Antonio Symphony, didn’t disagree. He said money-raising deficiencies and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic left the organization no choice but to pursue drastic cuts.

“It’s well known that we are understaffed, both on our revenue-generating side as well as on our operations side,” Cowart said. “We have a current administrative staff of 12 folks, including me, where 10 years ago, we were at 20.”

When Cowart worked in Atlanta, that city’s symphony had some 20 development staffers and a budget of between $25 and $30 million. Over the past decade, the San Antonio Symphony has made do with just three development staff and struggled with consistent turnover.

The San Antonio Symphony’s financial problems are longstanding. So much so that Goree said friends asked her whether she was crazy when she accepted an offer to come to the city in the 1980s. She and the other musicians are currently paid just $35,774, well below average compensation for full-time orchestra members in other cities.

Despite that, the symphony has continued to play at a level on par with better-financed counterparts in Dallas, Houston, Fort Worth and elsewhere.

“The San Antonio Symphony has played far beyond its compensation for decades, and what they are doing is destroying that,” said Ken Freudigman, the symphony’s principal cellist. “If they get their way with an A/B contract, you won’t get players of any quality who will come. It’s not going to happen.”

Looking elsewhere

It’s not just musicians facing part-time work who are considering leaving. Freudigman, who’s played with the symphony for more than two decades and co-founded the Camerata San Antonio chamber ensemble, said he’ll audition for other symphony jobs this year no matter how or when the strike is settled.

Like many colleagues, Freudigman spent the past four months playing with symphonies in other cities, including Atlanta, which he said has been an eye-opening experience.

“I’ve had an amazing time there,” he said. “They’ve been so welcoming. The biggest thing that I’m noticing is the professionalism of the board and the staff and their commitment to the orchestra — their commitment to the musicians.”

Such departures would leave a deep mark on the San Antonio symphony itself. They would also dramatically change the city’s larger music community.

Beyond his role in the orchestra, Freudigman teaches. One of his students, Vincent Garcia-Hettinger, told the Current that without the leadership of symphony musicians, “music education in San Antonio would suffer a huge blow that would be felt for generations to come.”

Daniel Taubenheim, the associate principal trumpet, is another example. He took a one-year contract to play with the Phoenix Symphony due to the strike. That meant giving up teaching positions at Trinity and St. Mary’s University, along with sessions with private students.

He plans to audition in Phoenix and elsewhere this year.

“We’re in the musical fabric, and we raise the level of music overall in this city by a significant amount,” Taubenheim said. “Without a professional full-time orchestra, that really is going to go away, sadly. There still will be music and music education, of course, but we are the top of the bar.”

Trinity professor Kneer agreed.

“Many of the symphony players go and teach and coach in local high schools, they coach and teach private lessons, and as a result I see that directly in the students who are coming to Trinity from San Antonio,” said Kneer, a violinist who’s played with the symphony in the past. “They’re being coached by symphony members, and it’s high-level training. The school is benefiting from that. All local universities are benefitting from that.”

‘Relationship cost’

The strike’s duration is also weighing on the San Antonio Symphony as an institution. Cowart said the ongoing lack of performances exacts a “financial cost as well as a relationship cost” on its reputation, locally and beyond.

Compounding the problem, J. Charlene Davis, a professor of business administration at Trinity, warned that the public’s sympathy in the matter is likely with the musicians, not the symphony itself.

“Who among us would feel great about being told, ‘Hey, we’re going to let go of a bunch of other folks who work with you, and we want you to do work, and, by the way, we’re going to reduce what we pay you’?” Davis asked. “So, I think public sympathy naturally goes out [to the musicians].”

Meanwhile, those musicians looking to leave are encouraging the younger ones who constitute the future of the orchestra to do the same.

“My advice to the young ones is go,” Freudigman said. “Leave now. If it’s not going to settle, go somewhere else where you can continue your career. Because with the direction that the board is taking right now, they have no career here — $11,000 is nothing. No healthcare. It’s untenable.”

MOSAS is resolute that it won’t agree to any contract that splits the orchestra between full-time and part-time musicians.

“When you have an orchestra and you’re making music, everybody matters,” Goree said. “To have colleagues who are paid poverty-level, insulting wages with no benefits, and to expect that we will sit next to them on stage knowing how they were treated, is misguided. That’s as nice a word as I can think of for it.”

Changing the model

Cowart said the Symphony Society is open to counterproposals that don’t include splitting the orchestra between full-time and part-time musicians — if it can cut costs. The symphony’s first offer last fall, which MOSAS rejected, was to slash all 72 musicians’ base pay by 50% to just $17,710.

“We’ve made incremental changes to the organization for over a decade, and we’ve basically gotten to a point where … the model that we had fundamentally didn’t work anymore,” Cowart said.

Many musicians and supporters want to see the symphony engage in emergency fundraising to finance a full orchestra, then begin bringing in new sources of money to ensure its long-term stability.

But Cowart said emergency fundraising has historically gotten the symphony into trouble. The organization needs a reset, he said.

“We have this continual history of almost shutting our doors, and those more sophisticated individual and institutional donors, who really pore over our audited financials and are looking at our results, are gradually, over time, stepping away from the organization,” Cowart said.

The symphony, according to Cowart, needs time to rebuild its relationships with major donors, cultivate new ones and shore up its finances. COVID-related grants and bailout money have helped, but they haven’t fundamentally changed the symphony’s position.

Forced to rebuild

But the musicians said they don’t have time to wait. The Symphony Society canceled their health insurance in October, which Goree called one of many acts of “blatant disrespect” from management.

If musicians depart and the quality of the symphony drops, it will be that much more difficult for the Symphony Society to raise the dollars it needs, they warn.

“The amount of time, money, and effort it would take to recoup [the current] level, in my opinion, in my experience, would be years,” Kneer said. “Many, many years, if you scale it down to skeletal and hope to rebuild it.”

Kneer said that he believes some members of the symphony’s board want to maintain the quality of the orchestra, while others are less committed and willing to sacrifice its reputation. Allowing that second option to win would be a grave mistake.

“We can’t give up on what we have,” Kneer said, pointing to the symphony’s long, storied history. “We just can’t. I think it would be a very sad day to let a legacy like the San Antonio Symphony slip through our fingers.”

Stay on top of San Antonio news and views. Sign up for our Weekly Headlines Newsletter.