Housing and neighborhood issues are never far from the headlines in San Antonio, and they are among the most important challenges that a new mayor and council will face after the May 2015 election. There are issues of development and land-use changes, like the closing of Main Avenue for the new near-downtown H-E-B store. There are issues of zoning and historic preservation. And there is the issue of neighborhood change—particularly the threat of "gentrification" in the wake of major public investments like the River Walk extensions and public incentives tied to former Mayor Julián Castro's "Decade of Downtown."

But a recent report from economist Joe Cortright and Cityobservatory.org, a new urban research website funded by the Knight Foundation, sheds real light on our "biggest urban challenge," the persistence and spread of high-poverty urban neighborhoods. Tracing change in urban neighborhoods using Census data from 1970 to 2010, Cortright has found that those neighborhoods that had high-poverty populations in 1970 largely remained poor in 2010, with only a small proportion "rebounding." And those poor neighborhoods experienced significant population losses over this 40-year period.

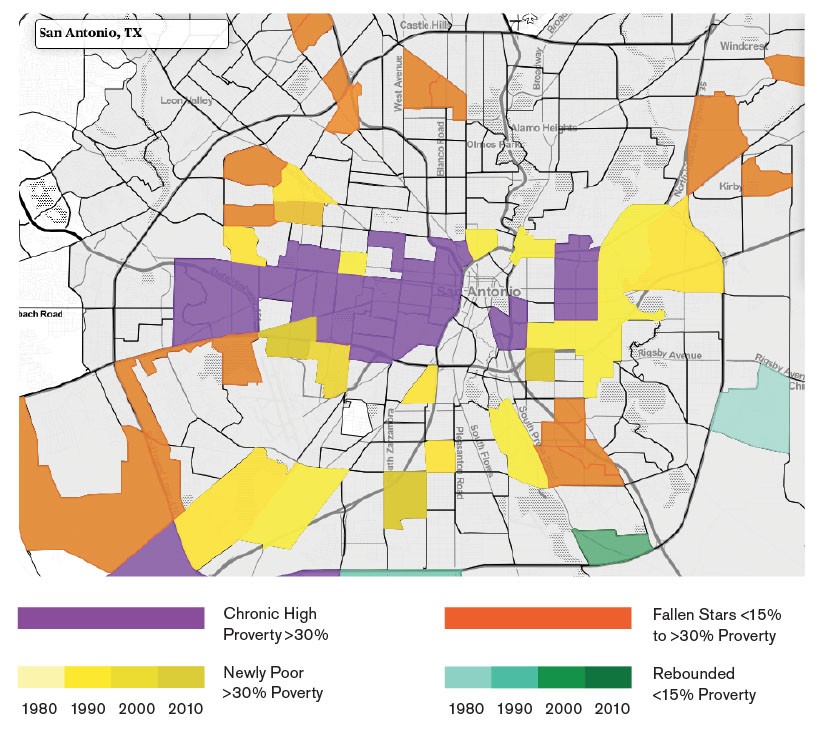

In addition to "chronic poverty" areas, there are also a substantial number of "fallen stars"—areas that have become poorer since 1970 and that by 2010 were home to more than 4.5 million people nationally.

Cortright was able to identify some big city neighborhoods that rebounded over time. They were concentrated in a relative handful of major metropolitan centers—New York City, Chicago, New Orleans (probably a result of changes following Hurricane Katrina) and Washington, D.C. Cortright ultimately concludes that although neighborhood change is a constant: "While the abrupt transformation of a few formerly high-poverty neighborhoods captures our attention, it masks a larger and more troubling trend—the steady expansion of new high-poverty neighborhoods."

The findings for the San Antonio metro area are striking. We had 38 Census tract areas with concentrated poverty in 1970, a total that grew to 66 by 2010, housing a total of almost 98,000 poor people. In contrast, there were only three "rebounding" neighborhoods that saw a significant reduction in poverty from 1970 to 2010. The map that accompanies the San Antonio data on the Cityobservatory.org website makes it abundantly clear what's happened. Those three "rebounding" census tracts are on the south and east around Loop 410, a result of new construction and development around Brooks City Base and the new Toyota plant. The inner city is a very different story. The areas of concentrated poverty on the near east and west sides remain—albeit with a drop in their populations. Further out, but still well inside Loop 410, are a host of "newly poor" and "fallen star" neighborhoods that have seen often dramatic increases in their levels of poverty.

Media and politicians have given a lot of attention to the issue of "gentrification" in San Antonio in recent months. Clearly, there is the threat of destabilizing change for some inner-city neighborhoods. There is the reality of the displacement suffered by the residents of the Mission Trail Mobile Home Park. Yet our discussion of neighborhoods should not just be limited to those cases. We have a larger, more serious, more persistent problem of chronic poverty and population loss in our inner city, a situation unlikely to be altered by City incentives for new downtown housing or the cry for a "Decade of Downtown." Whoever ultimately chooses to run for mayor (and City Council) owes the local electorate an honest and forthright statement of how she or he will deal with the harsh dual realities of chronic poverty and neighborhood decline in our community. The rhetoric of a "City on the Rise" may sound wonderful to local boosters, but it won't solve our real, long-standing problems.